SG6 Pompeii. Tombs at Stabian Gate or Porta Stabia.

Tomb of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius.

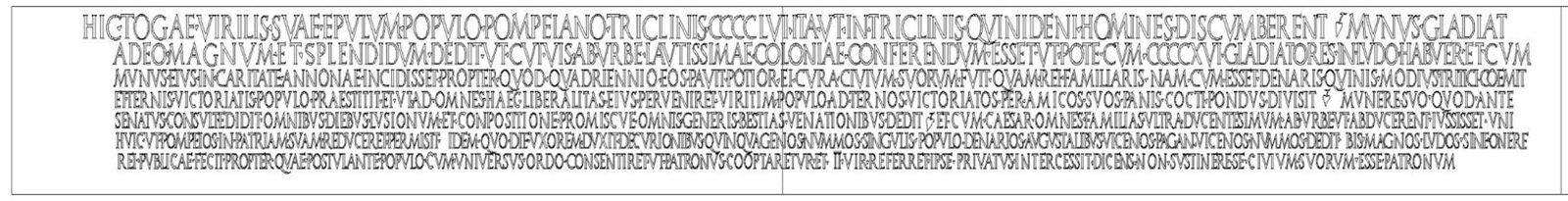

Tomb with 4-metre-long inscription with 7 rows and gladiator relief.

Excavated 2017.

This page has been reconstructed with photographs and press releases of the Parco Archeologico di Pompei. Our grateful thanks to the Parco Archeologico di Pompei for their permission to use this material.

Questa pagina è

stata ricostruita con fotografie e comunicati stampa del Parco Archeologico di

Pompei. Ringraziamo il Parco Archeologico di Pompei per il permesso di

utilizzare questo materiale.

Material used/Materiale

utilizzato

Studi del Prof. Massimo Osanna sul PAP

sito web

http://pompeiisites.org/comunicati/scoperta-tomba-monumentale/

http://pompeiisites.org/press-kit/cartella-stampa-la-nuova-tomba-di-porta-stabia/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alleius_Nigidius_Maius

https://diggingintojra.wordpress.com/2018/09/02/pompeii-inscription/

D’Ambrosio, A. and De Caro, S., 1983. Un Impegno per Pompei: Fotopiano e documentazione della Necropoli di Porta Nocera. Milano: Touring Club Italiano. (11OS).

Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2004. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, G17, p. 143.

Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

Journal of Roman Archaeology: vol. 31 (2018), pp. 310-322, fig. 4.

Osanna M., 2019. Pompei: Il tempo Ritrovato. Milano: Rizzoli, pp. 233-272.

English (our approximate translation)

PUZZLE FROM HISTORY

THE FUNERARY EPIGRAPH REVEALS IMPORTANT

INDICATIONS ON THE LAST DECADE OF POMPEII

The true story of the brawl at the Amphitheatre of 59

AD, with the exile of the magistrates

Reconstructed the context of the bas-relief with

gladiatorial scenes from the MANN

The

tomb

The excavation was connected with the refurbishing of

state-owned property in the San Paolino area just outside Porta Stabia.

A crew, restoring the 19th century palazzo planned to become the new library

and offices of the archaeological superintendency, came across a fragment of

marble while doing depth tests on the foundations.

Marble is very rarely used in Pompeiian funerary monuments, so archaeologists realized immediately that this could be something special and funds were immediately sought for an excavation.

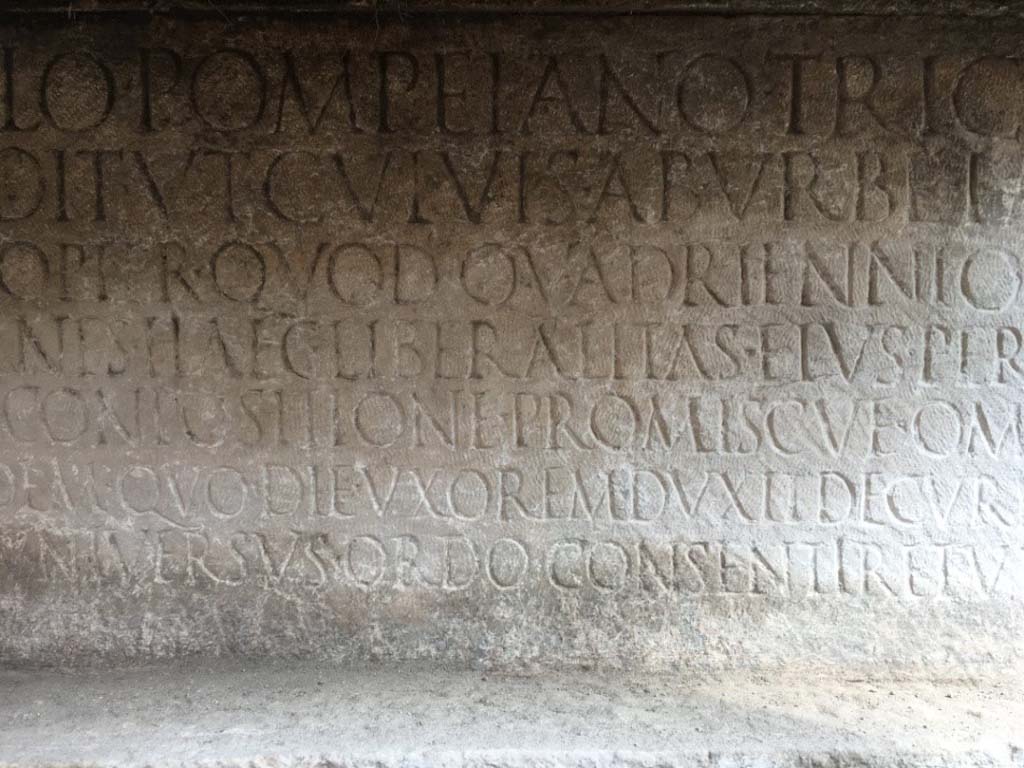

A marble monumental tomb was found, a quadrilateral with concave sides surmounted by a plinth, with the longest funerary epigraph ever found.

The tombstone was made shortly before the eruption that destroyed Pompeii in AD 79, which is why it is preserved in an exceptional way.

The inscription is over 4 metres long, in seven rows. It

does not include the deceased's name but describes in detail the life of the

man buried within it.

The new Porta Stabia monumental tomb includes an elegy to the deceased and the

most important parts of his biography, including his designation as duovir.

The inscription

According to Massimo Osanna, thanks to the citation of events in the deceased's life we have learned very important facts about the history of Pompeii, including in reference to the famous episode narrated by Tacitus that happened in Pompeii in 59 BC, when a brawl broke out in the amphitheatre during a gladiator show that led to an armed clash.

The event drew the attention of Emperor Nero, who ordered the Senate in Rome to investigate the incident.

Following an inquiry by the consuls, reports Tacitus, Pompeii residents were banned from holding gladiator shows for 10 years, illegal associations were dissolved and the organizer of the games - former senator from Rome, Livineio Regulo - and all the others who were found guilty of incitement were exiled.

The inscription complements the information given by Tacitus and refers for the first time to the exile imposed on some magistrates, the duoviri of the city.

The new tomb reveals significant new data on the history of the last decades of Pompeii.

It has a sepulchral inscription in the form of res gestae (that is, describing the

major things done in life).

Burial inscriptions, notoriously, contain the name of the deceased, may or may not indicate age, social status, career or other biographical information.

For magistrates, the citation of the activities carried out is summarized in the cursus honorum (the public career). Other references are rather rare.

In this case instead the praise of the deceased is made, of which in Pompeii there is nothing comparable.

It remembers actions and activities carried out during important moments of the life of the deceased:

He hosted a great banquet to celebrate his assumption of the toga virilis (“toga of manhood”) when he was 15-17 years old.

456 triclinia (formal dining rooms) accommodated thousands of members of the public.

An incredible 416 gladiators took part in games, far greater than the normal 30 or less that fought in the regular games in Pompeii.

His wedding which hosted a large banquet.

His largess

Events celebrated with acts of munificence.

Public banquets,

His generous gifts of silver coin to the people

Moneys given in support of magistrates and guilds

and above all great games with fights between gladiators and wild beasts.

The political and religious offices he held

He was one of the duoviri quinquennales (the two heads of the city administration elected every five years with additional powers to update the census)

He was acclaimed by the people as patronus of the city, which he humbly declines in the last line of the inscription because he is unworthy of so great an honour.

All this was widespread practice among property owners to gain prestige and promote their political career.

It is no coincidence that, as the inscription shows, the deceased then held the office of duovir.

The amphitheatre riot of AD59

In the inscription, which completes the information of

Tacitus, it refers for the first time to the exile that would hit even the two

top magistrates in office, the duoviri of the city.

Before now, the Tacitus passage, a fresco in the house of Actius Anicetus and

three graffiti found on walls at Pompeii were the only explicit references to

the amphitheatre riot of 59.

The funerary inscription adds a key piece of information about this event.

Thanks to the deceased’s personal relationship with Nero, he was able to persuade him to allow the two duoviri exiled as punishment for the brawl to return to Pompeii.

This is the only reference to the duoviri having been exiled as well as the only reference to the intercessionary role the tomb occupant played.

It opens up the possibility that he was involved in the softening and lifting of the 10-year ban on public events at the amphitheatre.

It’s known that some combat spectacles like animal hunts took place during the first three years of the ban, and it was lifted entirely in 62 A.D. to celebrate the restoration of the amphitheatre after the earthquake.

The inscription therefore provides unpublished data on an important moment in Pompeii's political and institutional history, confirming the scenario of a nasty intrigue only outlined by Tacitus.

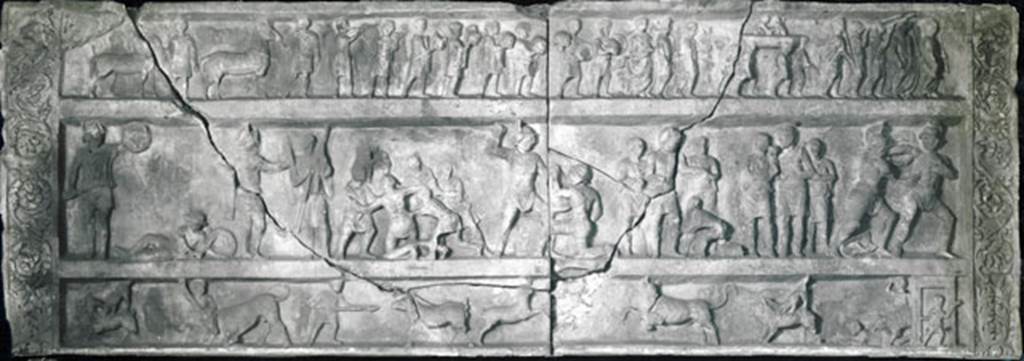

Gladiator relief in Naples Museum

Another remarkable thing, the discovery allows us to recontextualize an important piece, a gladiator relief with hunt scenes, kept at the Naples Archaeological Museum since the middle of the nineteenth century.

In view of what remains and the visible traces, as well as archive research that is still ongoing, it is more than likely that the top of the tomb, damaged by the construction of the San Paolino building in the nineteenth century, was completed with the gladiator relief preserved in MANN. If you evaluate the role that gladiatorial shows and venations have in praise, it can be assumed that the well-known relief with gladiatorial scenes and hunts with animals kept in Mann was placed there.

The relief has dimensions compatible with the monument, as its length is about 4 metres long, and would respond well in the theme to the role of the deceased as an extraordinary organizer of games.

Moreover, the relief, discovered by the superintendent Avellino in the 1840s, was found out of place (from the damage evidently suffered by the monument in the construction of San Paolino), precisely in the area of Porta Stabia.

SG6 Pompeii. Gladiatorial relief with hunting scenes from a tomb at Porta Stabia.

Now in Naples archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6704.

According to Emmerson, this relief measures more than 4 metres long and 1.5 metres high.

See Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

According to Osanna, the relief is in fact compatible with the monument, as its length is about 4 metres long and it was found out of place, precisely in the area of Porta Stabia.

Possible name of the tomb occupant

The inscription, unfortunately, is devoid of a name, which was probably placed in the top of the tomb, no longer preserved.

Given the type of the tomb, a

quadrilateral with concave sides surmounted by a plinth, in fact, it could

well be on a separate block, in larger characters.

An indication of name could be provided by the location of the tomb near the

one already discovered for M. Alleius Minius, an older schola tomb on the same

side as this.

To the Alleii family belongs Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius, one of the most prominent characters of the Nero-Flavian era.

Nigidius is an exponent of that new ruling class affirmed in the Nero-Flavian age and is repeatedly acclaimed in Pompeii as a prolific provider of games, indeed he can be said to have been the best-known among the gladiatorial impresarios of the city.

He was a freedman, the leading exponent of the ruling class of the last decades of the city's life, popular - thanks to the extreme social mobility of those years - thanks to the adoption by the important Alleii family.

His mother was Pomponia Decharcis and he was adopted at a relatively early age into the gens Alleii, his original family name being Maius, and it is possible that his mother was a freedwoman.

His mother was buried in the tomb of Eumachia, a wealthy and influential woman in the town, which suggests a close connection between the Alleii and Eumachia family.

The inscription on the herm was

POMPONIA DECH

ARCIS (Decharcis)

ALLEI NOBILIS

ALLEI MAI MATER.

Pomponia Decharcis, wife of Alleius Nobilis, mother of Alleius Maius.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2004. Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, G17, p. 143.

His father was Alleius Nobilis, a freedman who had made a fortune and had no bones about spending it on massively oversized celebrations to get his son started on a political career that would be largely based on throwing the biggest and best games in town.

His humble beginnings were no deterrent to Maius’ ascent, he became a priest of Caesar Augustus, became a personal friend to the emperor Nero and is referred to in Pompeian inscriptions as leader of the colony and the leading games-giver.

To him belonged the Insula Arriana Polliana (insula of the

house of Pansa) of which he rented out tabernae cum pergulis suis et cenacula

equestria et domus, as is reported in another epigraph referred to

him (CIL IV 138).

According to Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss/Slaby (See www.manfredclauss.de) this read

Insula Arriana

Polliana Gn(aei!)

Al<le=IF>i Nigidi Mai

locantur ex

<K=I>(alendis) Iuli(i)s primis tabernae

cum pergulis suis

et c{o}enacula

equestria et

domus conductor(is)

convenito Primum

Gn(aei) Al<le=IF>i

Nigidi Mai

ser(vum) [CIL IV 138]

According to Wikipedia this translates as

To let from July 1.

In the insula Arriana Polliana, property of Cnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius,

commercial/residential units with mezzanines, quality upper floor apartments and houses.

Agent: Primus, slave of Cnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius.

No Pompeiian is better documented in the archaeological record.

His name appears in 17 inscriptions, graffiti and edicts painted on the walls on the city.

Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius died a year before the cataclysmic eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii in 79 A.D.

The tombstone was made shortly before the eruption that destroyed Pompeii in 79 A.D., which is why it is preserved in an exceptional way.

If this character identification is correct, we have for the first time a monumental title since his career so far was known only through the inscriptions painted on the walls.

- END

-

Italiano

Da studi del Prof. Massimo Osanna

REBUS DALLA STORIA

L’EPIGRAFE FUNERARIA SVELA

INDIZI IMPORTANTI SUGLI ULTIMI DECENNI DI POMPEI

La vera storia della rissa

all’Anfiteatro del 59 d.C., con l’esilio dei magistrati

Ricomposto il contesto del

bassorilievo con scene gladiatorie del MANN

La nuova tomba

monumentale di Porta Stabia, realizzata poco prima dell’eruzione (motivo per

cui si conserva in maniera eccezionale), rivela nuovi rilevanti dati sulla

storia degli ultimi decenni di Pompei.

Si tratta di

una iscrizione sepolcrale nella forma delle res gestae

(ovvero recante la descrizione delle imprese realizzate in vita). Le iscrizioni sepolcrali, notoriamente,

contengono il nome del defunto, possono o meno indicare l’età, la condizione

sociale e la carriera o altre notizie biografiche. Per i magistrati la

citazione delle attività svolte si riassume nel cursus honorum (la carriera

pubblica); altri riferimenti sono piuttosto rari.

Nel nostro

caso invece viene fatto l’elogio del defunto, cosa che a Pompei non ha

confronti.

Sono ricordate

azioni ed attività realizzate in occasione di momenti importanti della

biografia del defunto: l’assunzione della toga virile e le nozze. Eventi

celebrati con atti di munificenza: banchetto pubblico, elargizioni di danaro in

argento; di monete ai magistrati delle associazioni, e soprattutto grandiosi

giochi con combattimenti tra gladiatori e con bestie feroci. Pratica diffusa

tra i possidenti per acquisire prestigio e promuovere la propria carriera

politica. Non è un caso che, come l’iscrizione riporta, il defunto abbia poi

rivestito la carica di duoviro.

Grazie alla

citazione di eventi topici della vita del defunto apprendiamo dati

importantissimi sulla storia pompeiana anche con riferimenti al famoso episodio

narrato da Tacito, Ann. XIV, 17, avvenuto a Pompei nel 59 d.C., quando durante

uno spettacolo gladiatorio scoppiò nell’anfiteatro una rissa che degenerò in uno

scontro armato. L’evento richiamò l’attenzione dell’imperatore Nerone che da

Roma incaricò il senato di indagare sul fatto. A seguito delle indagini dei

consoli, come riporta Tacito, ai Pompeiani fu vietato di organizzare altre

manifestazioni gladiatorie per 10 anni; le

associazioni illegali furono sciolte; l’organizzatore dei giochi, l’ex senatore

di Roma Livineio Regulo, e quanti avevano istigato il fatto furono esiliati.

Fin qui il passo di Tacito che però non è esplicito sulla sorte dei duoviri,

asserendo solo, in maniera generica, che tutti quelli coinvolti furono banditi.

Nella nostra

iscrizione, che completa le informazioni di Tacito, si fa riferimento per la

prima volta all’esilio che avrebbe colpito addirittura i due sommi magistrati

in carica, ossia i duoviri della città.

L’iscrizione

fornisce dunque dati inediti su un momento importante della storia politica e

istituzionale di Pompei, restituendo lo scenario di un torbido intrigo solo

adombrato da Tacito.

Altro dato

straordinario, la scoperta ci permette di ricontestualizzare un pezzo

importante finito al MANN alla metà del XIX secolo.

In considerazione di quanto resta e delle tracce visibili, oltre che delle

ricerche di archivio tuttora in corso, è più che verosimile che la parte

superiore della tomba, danneggiata dalla costruzione dell’edificio di San

Paolino nell’Ottocento, fosse completata con un rilievo conservato al MANN. Se

si valuta il ruolo che gli spettacoli gladiatori e le venationes hanno nell’elogio, si può ipotizzare che fosse ivi collocato il noto

rilievo con scene gladiatorie e di caccie con animali

conservato al Mann. Il rilievo ha infatti dimensioni compatibili con il

monumento, lungo com’è circa 4 m., e risponderebbe bene nel tema al ruolo del

defunto di straordinario organizzatore di giochi. Del resto

il rilievo, scoperto dal soprintendente Avellino negli anni ’40 del XIX secolo,

fu rinvenuto fuori posto (per i danni subiti dal monumento evidentemente per la

costruzione di san Paolino), proprio nell’area di porta Stabia.

SG6 Pompeii. Rilievo

gladiatore con scene di caccia da una tomba a Porta Stabia.

Ora al Museo archeologico di Napoli. Numero di

inventario 6704.

Secondo Emmerson, questo rilievo misura oltre 4

metri di lunghezza e 1,5 metri di altezza.

Vedi Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at

Pompeii's Porta Stabia:

Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

Secondo Osanna, il rilievo è infatti compatibile

con il monumento, in quanto la sua lunghezza è lunga circa 4 metri ed è stato

trovato fuori luogo, proprio nella zona di Porta Stabia.

Fotografia © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

Chi è, dunque, il defunto? L’iscrizione purtroppo

è priva dell’elemento fondamentale, che ipotizziamo fosse collocato nella parte

sommitale della tomba non più conservata. Data la tipologia del sepolcro, un

quadrilatero dai lati concavi sormontato da un dado, infatti, poteva ben

trovarsi su un blocco a parte, a caratteri più grandi.

Un indizio potrebbe essere fornito dall’ubicazione

della tomba in prossimità di quella già scoperta di M. Alleius Minius, una più

antica tomba a schola ubicata sullo stesso lato della nostra. Alla famiglia

degli Alleii appartiene Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius, uno dei personaggi più in

vista dell’età neroniana-flavia. Nigidius è un

esponente di quella nuova classe dirigente che si afferma in età neroniano-flavia, il quale risulta acclamato più volte a Pompei

proprio come prodigo dispensatore di giochi, anzi si può dire sia stato il più

noto tra gli impresari di spettacoli gladiatori della città. Il personaggio, un

liberto, è l’esponente principale della classe dirigente degli ultimi decenni

di vita della città, affermatosi – grazie all’estrema mobilità sociale di

quegli anni – grazie all’adozione da parte della importante famiglia degli

Alleii.

A lui apparteneva l’Insula Arriana Polliana

(insula della casa di Pansa) di cui mette in affitto tabernae cum pergulis suis et cenacula equestria et domus, come riporta un’altra epigrafe a lui riferita (CIL IV 138).

Se l’identificazione col personaggio è corretta,

abbiamo per la prima volta un titolo monumentale poiché la sua carriera era

finora nota solo attraverso le iscrizioni dipinte sui muri.

- FINE -

SG6 Pompeii. 2021. Gladiatorial relief with hunting scenes from a tomb at Porta Stabia. The background gives an indication of its large size.

According to Emmerson, this relief measures more than 4 metres long and 1.5 metres high.

The relief shows in three registers from top to bottom a procession, gladiator combat, and a venatio, or staged animal hunt. If this relief is funerary in nature, it is the largest known from Pompeii.

See Emmerson A. L. C., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia, Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, p. 78, fig. 1.

See Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at Pompeii's Porta Stabia: Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

According to Osanna, the relief is in fact compatible with this monument SG6, as its length is about 4 metres long and it was found out of place, precisely in the area of Porta Stabia.

Now in Naples archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6704.

SG6 Pompeii. 2021. Rilievo

gladiatore con scene di caccia da una tomba a Porta Stabia. Lo sfondo dà un'indicazione delle sue grandi dimensioni.

Secondo

Emmerson, questo rilievo misura oltre 4 metri di lunghezza e 1,5 metri di

altezza. Il rilievo mostra in tre registri dall'alto verso il basso una

processione, un combattimento di gladiatori e una venatio, o una caccia agli

animali messa in scena. Se questo rilievo è di natura funeraria, è il più

grande conosciuto da Pompei.

Vedi Emmerson A., 2010. Reconstructing the Funerary Landscape at

Pompeii's Porta Stabia:

Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 21, pp. 78, fig. 1.

Secondo Osanna, il rilievo è infatti compatibile

con il monumento SG6, in quanto la sua lunghezza è lunga circa 4 metri ed è

stato trovato fuori luogo, proprio nella zona di Porta Stabia.

Ora al

Museo archeologico di Napoli. Numero di inventario 6704.

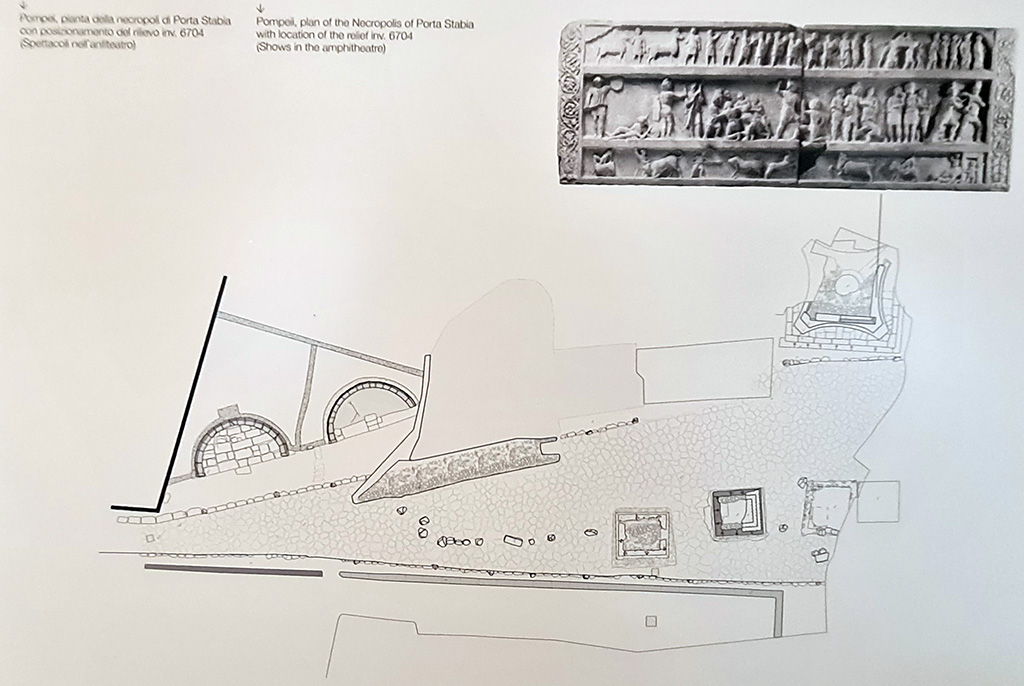

SG6 Pompeii. April 2023. Gladiatorial relief with hunting scenes from a tomb at Porta Stabia. Plan showing the location of the relief inv. 6704.

SG6 Pompei. Aprile 2023. Rilievo gladiatorio con

scene di caccia da una tomba a Porta Stabia. Pianta con posizionamento del

rilievo inv. 6704.

On display in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

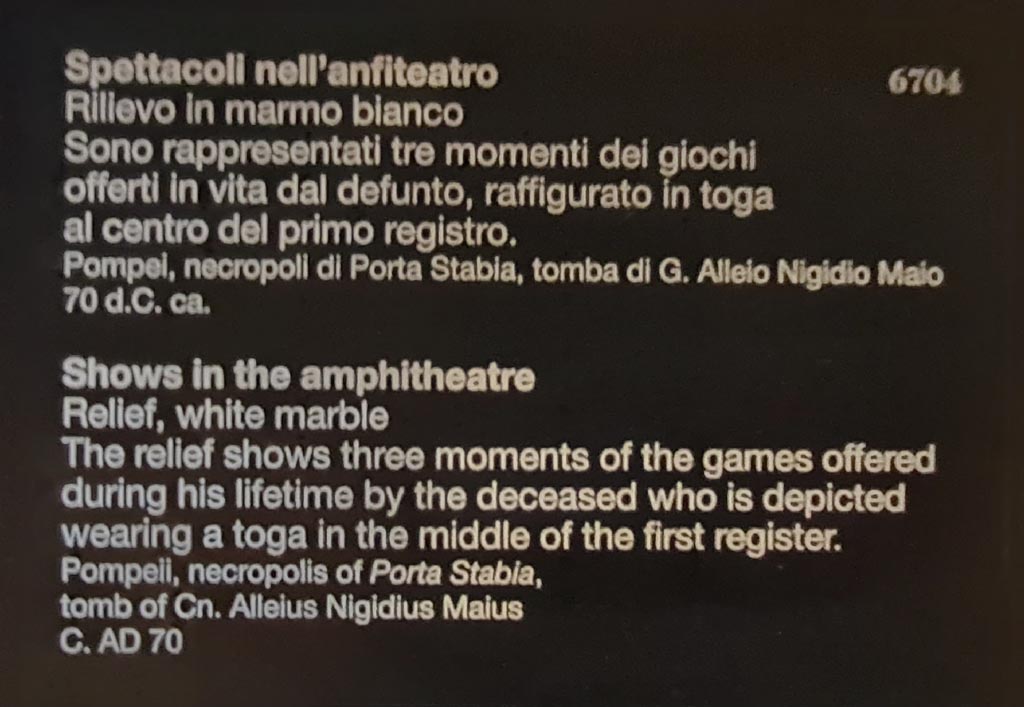

SG6 Pompeii. April 2023. Descriptive card for relief inv. 6704 in Naples Archaeological Museum.

Shows in the amphitheatre. The white marble relief shows three moments in the games offered during his lifetime by the deceased who is depicted wearing a toga in the middle of the first row.

This card clearly identifies the tomb as being that of Cn. Alleius Nigidius Maius.

Spettacoli nell’anfiteatro. Il rilievo in marmo

bianco rappresentati tre momenti dei giochi offerti in vita dal defunto,

raffigurato in toga al centro del primo registro.

Questa carta identifica chiaramente la tomba come

quella di G. Alleio Nigidio Maio.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG6 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail from upper row of figures in a procession, with the deceased shown in a toga, in centre. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG6 Pompeii. April

2023. Detail of procession with trumpeters from upper row, right-hand side. Photo

courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG6 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail of gladiator combat from middle row, right-hand side. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

SG6 Pompeii. April 2023. Detail of venatio or staged hunt from

lower row. Photo

courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Photographs/Fotografie

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Site of unnamed tomb with 4-metre-long inscription next to building in San Paolino area near Porta Stabia.

The top of the tomb is damaged, which was evidently suffered in the construction of the San Paolino building in the 19th century.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Unnamed tomb, looking east to palazzo and showing three of the curved sides.

The tomb is still partially buried, incorporated in the

foundations of the historic building, the current headquarters of the

Soprintendenza offices, making the surprise of such a discovery even more

unique, being only a few metres from those who work daily on the site.

See Osanna M.,

2019. Pompei: Il tempo Ritrovato. Milano: Rizzoli, pp. 235, fig. 3.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Unnamed tomb looking south. The north side has the 4-metre-long inscription.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Showing closeness to the 19th C. palazzo.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Curved west and south sides. Photograph © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. East end of north side during excavation.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. North side during excavation with tufa blocks underneath.

Photograph © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Curved north side with 4-metre-long marble inscription above.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Curved north side. Photograph © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. 4-metre-long inscription on north side with cornice above and damaged top area.

Photograph © Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. 4-metre-long inscription, showing 7 rows, in the form of a res gestae (life achievements).

It does not include the deceased's name but describes in detail the life of the man buried within it.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Detail of part of the inscription showing the 7 rows.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2018. Transcript of the inscription showing the

7 rows. Photograph © Parco

Archeologico di Pompei.

See Journal of Roman Archaeology: vol. 31 (2018), pp. 310-322, fig. 4.

The inscription

The full inscription reads

Hic togae

virilis suae epulum populo pompeiano triclinis CCCCLVI ita ut in triclinis

quinideni homines discumberent (hedera). Munus gladiat(orium) / adeo magnum et

splendidum dedit ut cuivis ab urbe lautissimae coloniae conferendum esset ut

pote cum CCCCXVI gladiatores in ludo habuer(it ?) et cum / munus eius in

caritate annonae incidisset, propter quod quadriennio eos pavit, potior ei cura

civium suorum fuit quam rei familiaris; nam cum esset denaris quinis modius tritici,

coemit / et ternis victoriatis populo praestitit et, ut ad omnes haec

liberalitas eius perveniret, viritim populo ad ternos victoriatos per amicos

suos panis cocti pondus divisit (hedera). Munere suo quod ante /senatus

consult(um) edidit, omnibus diebus lusionum et conpositione promiscue omnis

generis bestias venationibus dedit (hedera) / et, cum Caesar omnes familias

ultra ducentesimum ab urbe ut abducerent iussisset, uni / huic ut Pompeios in

patriam suam reduceret permisit. Idem quo die uxorem duxit, decurionibus

quinquagenos nummos singulis, populo denarios augustalibus vicenos pagan(is)

vicenos nummos dedit. Bis magnos ludos sine onere / rei publicae fecit; propter

quae postulante populo, cum universus ordo consentiret ut patronus cooptaretur

et IIvir referret, ipse privatus intercessit dicens non sustinere se civium

suorum esse patronum.

https://diggingintojra.wordpress.com/2018/09/02/pompeii-inscription/

Tentative preliminary Italian translation

Costui in occasione

della sua toga virile offrì alla cittadinanza pompeiana un banchetto con 456

triclini in modo che su ciascun triclinio trovassero posto quindici uomini.

Offrì uno spettacolo gladiatorio di tale grandiosità e magnificenza da poter

essere confrontato con qualsivoglia nobilissima colonia fondata da Roma poiché

parteciparono 416 gladiatori.

Ora, poiché la

sua munificenza era coincisa con una carestia, per questo motivo, per un

quadriennio, li alimentò; per lui la preoccupazione per i suoi concittadini fu

superiore a quella per il suo stesso patrimonio; infatti essendo quotato un

moggio di frumento a cinque denari, ne acquistò e lo mise a disposizione del

popolo a tre vittoriati (al moggio). E affinché a tutti pervenisse questa sua

liberalità, distribuì alla cittadinanza individualmente attraverso i suoi amici

una quantità di pane cotto equivalente a tre vittoriati.

In occasione del

suo spettacolo che aveva organizzato prima del senatoconsulto, per tutti i

giorni dei giochi, per ogni tipo di combattimento (in programma) fornì animali

di tutte le specie senza distinzione alle cacce.

E poiché Cesare

aveva dato ordine di deportare dalla città oltre il duecentesimo miglio tutte

le famiglie (condannate), concesse solo a costui di ricondurre in patria i

Pompeii.*

In occasione del

suo matrimonio elargì la somma di cinquanta nummi a ogni singolo decurione, per

quanto riguarda il popolo venti denari per ciascun augustale e venti nummi per

ogni pagano.

Organizzò in due

occasioni grandi spettacoli senza onere alcuno per la comunità.

Per tutte queste

cose, in base alla richiesta della cittadinanza, essendo d’accordo tutti i

decurioni che fosse cooptato come patrono, mentre il duoviro riferiva

(all’assemblea) egli stesso, da privato cittadino, oppose il suo veto,

affermando di non essere in grado di essere patrono dei suoi cittadini.

A first discussion and interpretation is given by Massimo Osanna in JRA 31.

See Journal of Roman Archaeology: vol. 31 (2018) (pp. 310-322).

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. The

new tomb from the northwest showing location of inscription as it appears on

site.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

See Journal of

Roman Archaeology: vol.

31 (2018), Fig. 4.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. 4-metre-long inscription, showing 7 rows, in the form of a res gestae (life achievements).

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Looking north across damaged top of tomb, towards Porta Stabia and other tombs.

The damage was evidently suffered in the construction of the San Paolino building in the 19th century.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Looking north-east into burial chamber.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Pompei.

Skeletons

SG6 Pompeii. 2017. Skeletons found south of unnamed tomb. Photo courtesy of La Gazzetta Italiana.

During the excavation, there were also found visible traces of the Pompeiians fleeing from the famous eruption of 79 A.D.

Above the layer of over two metres of the lapilli that covered this part of the ancient city, were visible traces of ruts and furrows of wagons.

This may be connected to the discovery of skeletons not far away from there.

See http://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/history-culture/8557-a-new-discovery-in-pompeii-an-italy-that-keeps-surprising